Professor Ellison has been called before the administrators at his Los Angeles-area prestige university. He’s offended yet another easily offended student. Ellison asks why they’re so “delicate” these days, only for the administrators to lightly in tone (but demanding in intent) ask him to take some time away from the classroom.

What got him in trouble? In a classroom discussion of Flannery O’Connor’s role in southern fiction, Ellison wrote “the artificial n——r” on the whiteboard. An offended student raised her hand to tell the professor her difficulty with the “wrong” word on the board. Ellison responded dryly that it’s not wrong, that it has two gs.

Ellison’s time away from campus begins in Boston where he’s set to attend a major book festival. The problem is that Ellison hates going to Boston, and he hates it because he can’t stand his family (prominent medical doctors for the most part) that is still largely based there.

Still, Ellison has the manuscript of his latest novel with publishers (so far they’re rejecting it) who will surely populate the conference, so he grudgingly goes himself. As an author of mostly unread novels, Ellison will be on a lightly attended conference panel. This experience has the grouchy Ellison even more perturbed.

Worse, he subsequently walks into a reading by author Sintara Golden. Golden is black, wears Claudine Gay glasses, attended hyper left-wing Oberlin in Ohio, and moved to New York City “the day after graduation” so that she could start work for a prominent publisher. Golden’s new novel, titled We’s Lives In ‘Da Ghetto, is all the rage at the festival.

Golden, who speaks impeccably, explains to the nearly all-white audience that she felt readers needed a more realistic portrayal of black life. From there, Golden’s reading descends into the broken English that the far-from-the-ghetto raised Golden plainly imagines is a portrayal of “real” black life. Ellison is offended, and worse, frustrated as the huge crowd of mostly white readers gives Golden a standing ovation for what they imagine is her remarkable verisimilitude.

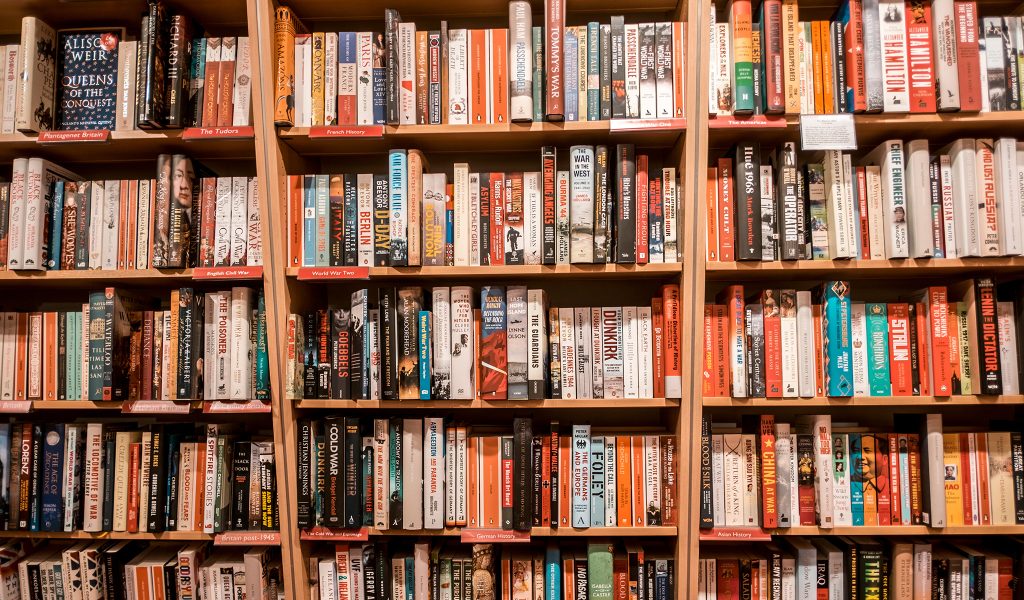

A few scenes later, Ellison can be found in a Boston bookstore doing as authors do, looking for his own books. If there’s an unreal scene in the film it’s this one, and that is so not because the scene isn’t funny. It’s laugh out loud funny, but writer and director Cord Jefferson might agree that the scene violates the popular truth supposedly first uttered by the late and legendary Random House editor Jason Epstein that “no author since Homer has ever found his book in a bookstore.”

For the purposes of this great film, it’s fortunate that Ellison found a stack of his own books, and that he routinely finds his books in bookstores. That is so because it sets him up to complain to a low-level employee that his novels should not be in the African American literature section since they have nothing to do with race. It seems this dressing down of junior employees is the norm for Ellison, and then it gets worse. While attempting to move his novels to the novel section of the bookstore (he’s told they’ll just be moved back), he happens on a full, standalone display for Golden’s We’s Lives in ‘Da Ghetto.

My guess is that I didn’t do a credible or passably interesting job of hiding the punchline or the “surprise revelation” that comes next, but Professor Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison is black. Played by the spectacular Jeffrey Wright (Asteroid City, Hunger Games, Basquiat), Monk doesn’t hide from his color as much as he doesn’t want to be defined by it. He is a writer, not a black writer. He doesn’t write about life in the streets, or racial issues, or anything else that racially focused whites (whether left or right) want black people to write or think about. One guesses that if the character were an economic commentator, that he would similarly not write about economics as it relates to blacks. Amen to that!

Without giving much more away, from the visit to Boston a bigger family story emerges for Monk. Death of a sister, the onset of dementia in his mother, divorce for Monk’s plastic surgeon brother, and upper strata financial worries reveal themselves. Amid this, the endlessly cranky Monk starts writing his own version of We’s Lives in ‘Da Ghetto late one night. It’s titled My Pafology, and Monk submits it to his agent as a joke and also a comment about the kind of literature that guilty, left-leaning white readers are really interested in.

Monk’s agent doesn’t just read the manuscript, he reads it and submits it to publishers, including publishers who’d always rejected Monk’s race-free novels. Those who formerly didn’t have time for him subsequently court him, and with big checks in hand. Stagg R. Leigh, Monk’s pseudonym used for My Pafology, is a criminal with a rap sheet. The police are said by Stagg to be in hot pursuit of him as My Pafology is going to the printer, which makes the novel even more of a hot commodity, so much so that Stagg demands a dealbreaking title change that his obsequious publisher agrees to. Then Hollywood calls with an even bigger check in hand to bring this future bestseller to the screen.

Some, conservatives in particular, will read this write-up and be interested in its portrayal of guilty white left wingers, the black professor who disdains their guilt, along with the film’s proper ridicule of white guilt as an excuse for the pursuit of diversity for the sake of diversity. It’s all there, including Monk being asked to serve on a prestigious book-prize panel that will decide the year’s best book. You guessed it, the organization behind the prominent award wants a bit more “diversity.” Yes, conservatives will enjoy the film. Big time. It’s fun to see black people mock the same political correctness that members of the right have long similarly mocked.

At the same time, the view from this right-of-center writer is that while conservatives will surely laugh endlessly during this hilarious and extraordinarily well written film, that it’s brilliantly funny for everyone, including left-of-center types. There’s a family story that the great Kyle Smith viewed as filler, but that worked for me as a way of explaining Wright’s character, and the why behind Wright’s character, in entertaining fashion.

Additionally, it will be said here that conservatives shouldn’t walk out of the theater with too smug of a countenance. This is based on their own routine desire to feature black conservatives in their newspapers, magazines and television shows every time a racial situation reveals itself, the tendency of white conservatives to cheer a black person’s expressed conservatism regardless of whether it’s well-reasoned (I once witnessed a right-leaning black judge give a wholly unremarkable speech that ended with a standing ovation…), not to mention the growing desire of conservatives to deify the “canceled” members of their own flock (with book deals, awards, and well-paid jobs) in the way that dopey left wingers deify anything that’s “Black,” and no matter how ridiculous it is.

Back to the fun within what is the best film of the year in a year that was very good for movies, the publisher of the formerly titled My Pafology submits Stagg Leigh’s novel. Monk’s panel largely receives it with rapture. To attempt to write out the excitement of the left-leaning, very white panelists would be to diminish what is so well written. Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction is topical, the big laughs are constant, and if asked it will be my favorite film of 2023, by far. Run, don’t walk.

Republished from RealClear Markets